To which pan-africanism do you belong?

And here is a secondary title

My latest solo exhibition "STEAL LIFES" took place at the Maia Muller Gallery in Paris from April 10 to June 1st. Two things to read about this exhibition.

A short introduction by myself | STEAL LIFES

In my youth I used to be optimistic, I wanted to change the world. I realize today that the world is a dangerous place managed by criminals. I turned "peptimistic". I don't want to change the world anymore but I don't want the world to change me, cause the one who wants to change the world is suspect.

That's where the idea for "Steal Lifes" emerged, literally "stealing lives!", which refers to a situation where to earn the right to live, one must become an outlaw, a thief, a stateless person, an illegal immigrant, an economic migrant,…etc. This title is also a reference to the "still life" painting genre. I use a still life and a self-portrait to talk about the world today.

Preface by Sarah Ligner - Responsable of the heritage unit Historical and Contemporary, department of heritage and collections of the Quai Branly Museum

"Thus irony always beats despair to it: it does a pirouette and – in less time than it takes to utter – it has already evaded the cause of our torment; right under the nose of fate, we have become a gardener, a surveyor or a violinist, and our person is smuggled away under the greatest variety of masks "(Vladimir Jankélévitch, Irony).

The still life, a Western pictorial genre, probes the hieratic character of elements of nature and of man-made objects. The linguistic variations - still life, nature morte, Stillleben - insist sometimes on the inanimate nature of objects and sometimes on their immobile and silent dimension. This pictorial genre, however, can be extremely expressive when it expounds on the fleetingness of existence. At the School of Fine Arts in Khartoum where Hassan Musa studied in the early 1970s, categories ofWestern painting such as still life, portraiture or landscape were presented as models. They continue to haunt his iconographic repertoire. But these are just a few images among others that the artist has summoned at will for several decades to create a chronicle of our contemporary societies.

Hassan Musa brings together still life and assassination: the frugality of the last meal of Christ is eclipsed by the globalisation of fast food under the banner "Eating kills", while the immaculate flesh of the odalisque in her harem is surrounded by burgers and fries. Hassan Musa dishes out the emblems of consumerist and capitalist societies. An expert in the field of diverting images, he also likes to make some shifts in the art of language. From still life to steal lifes, he refuses the immobility of the world to tackle instead its endless upheavals, giving rise to bitterness in the face of the lives that are revealed.

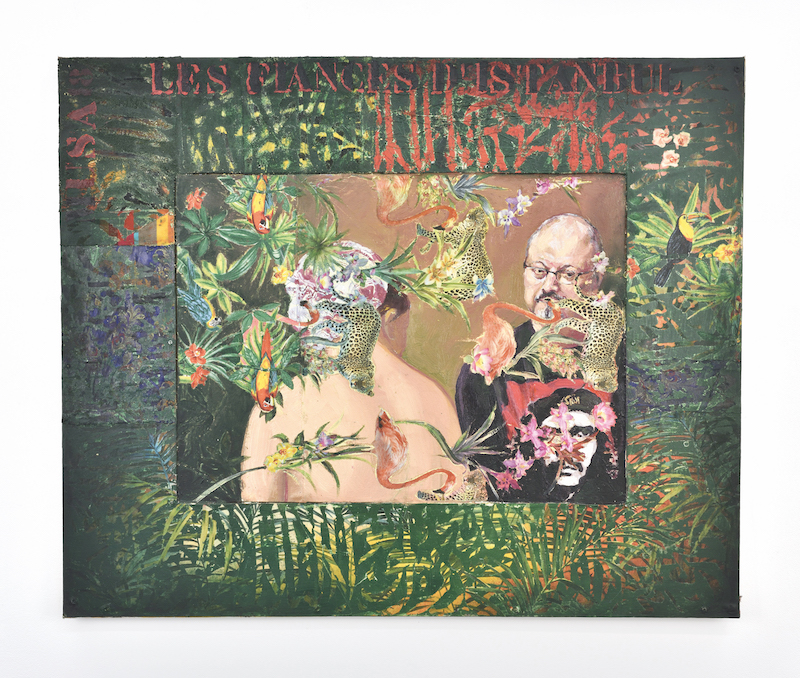

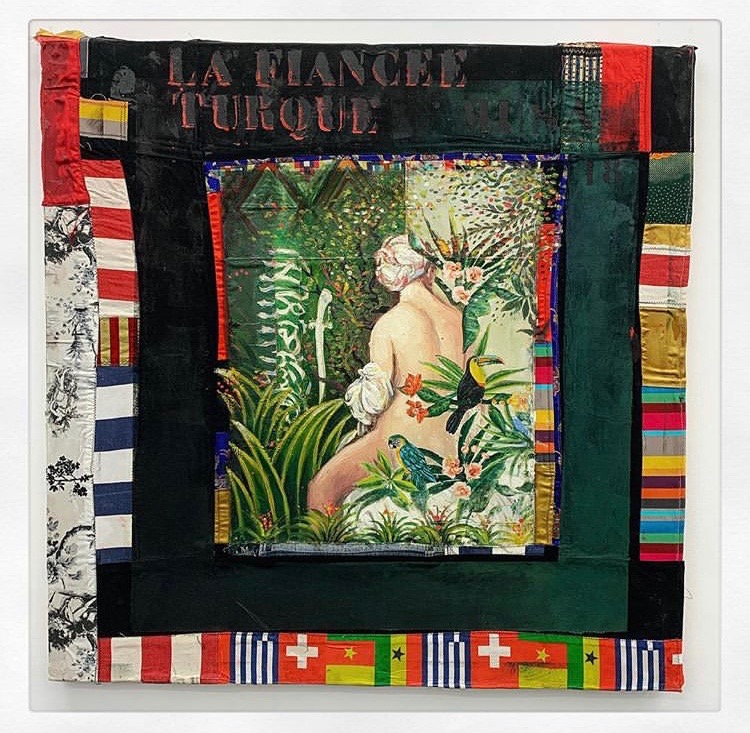

Hassan Musa continually battles with the East to reveal the fabric woven yesterday by Western imperialism and shaped today by the geostrategic stakes of oil. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres provides the characters, borrowed from the Louvre’s picture rails. Hassan Musa has already entrusted the role of The Great Odalisque to Osama bin Laden. This time, the Valpincon Bather is the Turkish bride of Jamal Khashoggi. Having passed from state media to dissidence, the Saudi journalist had gone into exile in 2017 in the United States before being murdered in 2018 in Istanbul. His death caused a major diplomatic crisis. Is he really a martyr of freedom of expression? In a reversal of the honorific portrait, Hassan Musa asks himself what fabric those who are erected as icons are really made of.

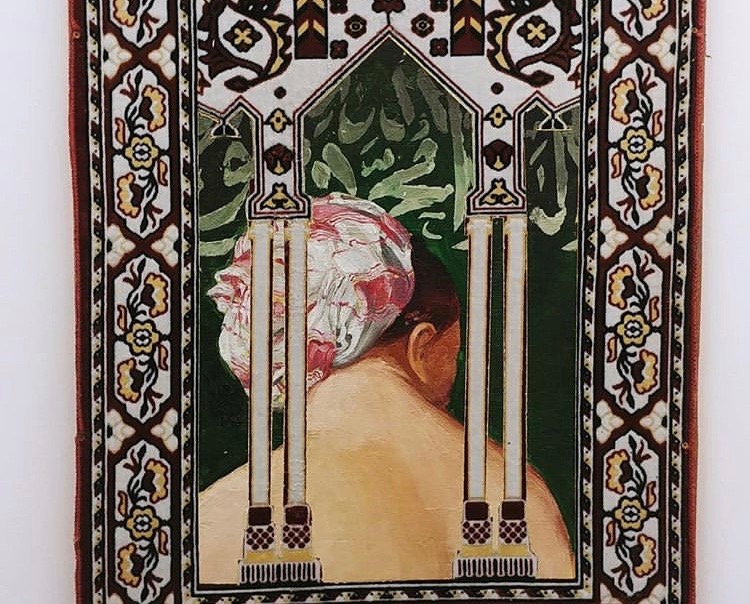

To mention fabric is to delve into the artist's studio and observe his delight at cutting pieces of textiles, seizing their printed patterns, sewing them, combining them or allowing oil paints to blossom at their side. A cloth representing chickens directsHassan Musa towards another fowl: from Leda's thighs emerges a swan, which is none other than the master of Olympus, Zeus, come to visit his lover. As for the famous, green, American banknote, it is lost in the luxuriant jungle of Le Douanier, HenriRousseau. In the centre, Josephine Baker is the snake charmer. Missouri music-hall figure, she set interwar Europe aquiver with her Negro Revival. Hassan Musa transposes her to the stereotype of "wild" life in an indistinct jungle but arms her with aKalashnikov for her defence. Interrogating the construction of characters of history and of imagination leads us to the artist himself. During his career inSudan and then in France, Hassan Musa has time and again come up against questions relating to identity. In the artistic field, he has denounced the confinement of creativity to geographical norms. Rather than letting himself be confined in his self portraits, he prefers instead to deconstruct his face, the features of which are cut in pieces and added to those of other images.Wary of any taxonomy, Hassan Musa weaves eras and genres and rejects the hierarchy of images, all in joyful freedom, where the irony works to indicate what, in humanity, withers.Sarah Ligner is Head of the Historic and Contemporary Globalisation Heritage Unit ;Department of Heritage and Collections, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.