NAGE ICARE [Solo show]

Galerie Maïa Muller, Paris - 02.09 to 07.10.2017

This past, the Negro’s past, of rope, fire, torture, castration, infanticide, rape; death and humiliation; fear by day and night, fear as deep as the marrow of the bone; doubt that he was worthy of life, since everyone around him denied it [...] this past, this endless struggle to achieve and reveal and confirm a human identity, human authority, yet contains, for all its horror, something very beautiful. - James Baldwin - The Fire Next Time (1963).

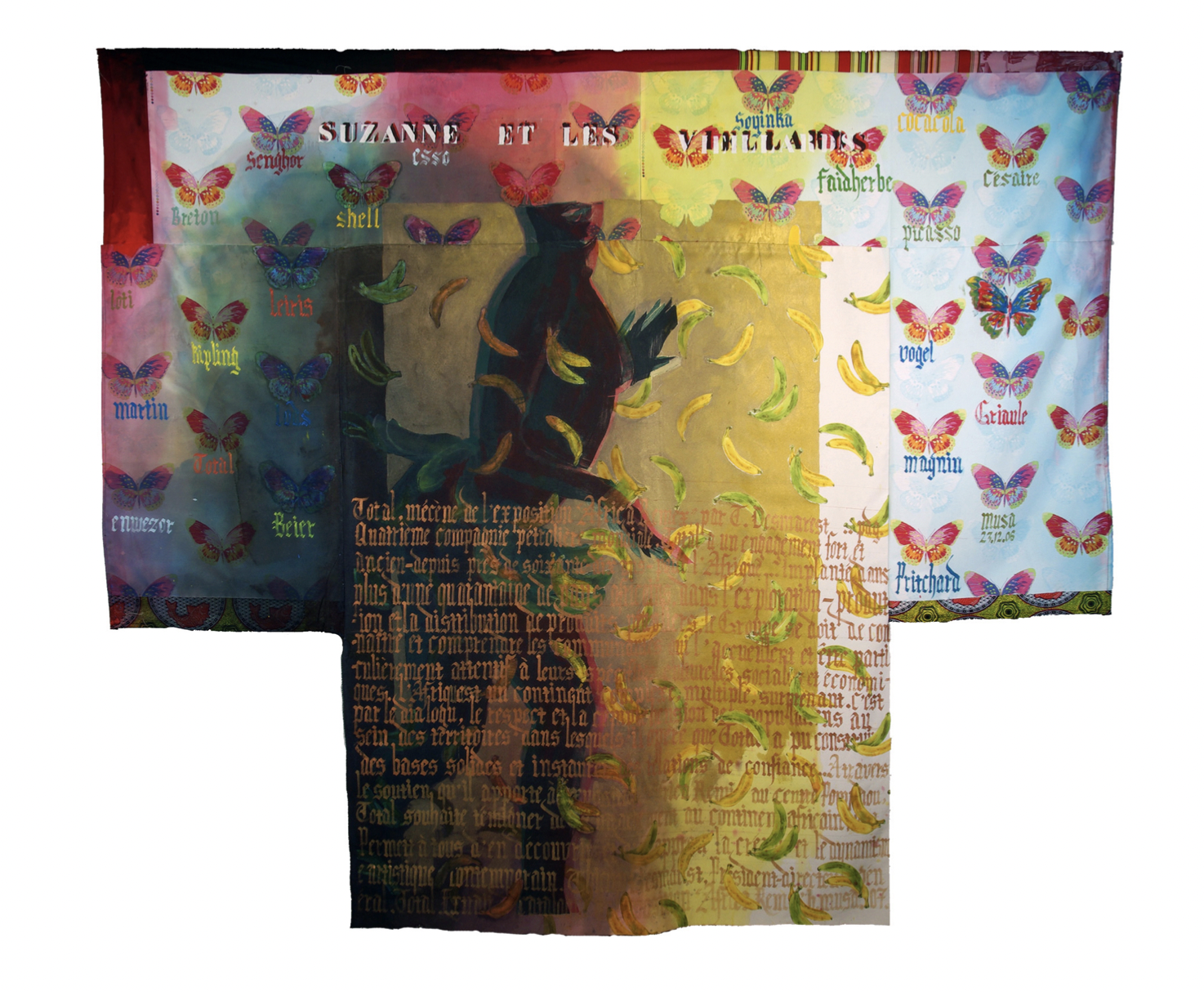

In 1975 Hassan Musa began painting large format whilst working for a Sudanese television channel. From 1980, he collaborated with a dance and theater company. Like in a theater, he looks attentively at the world, its history and its news, which, in his paintings on fabrics, he fuses with humour, poetry and irony. Everything starts with a pattern printed on cloth; a fruit, an animal, a motorcycle, a flower... The motif generates a reaction, a scene most often consisting of a central figure. Hassan Musa has repeatedly introduced known characters: Osama bin Laden, Josephine Baker, Barack Obama or even himself. They are each connected to printed or painted patterns, signs that initiate a disturbance, a critical gap. The signs call for a collective memory and imagery that interweaves stereotypes, references to current events, mythologies, art and religions. In this way, the artist invokes different forms of ideologies on which cultures are based. He readily associates Western signs with Oriental signs in order to denounce with obstinacy the danger of universalism and therefore of Western imperialism.

François Jullien asks the question: "How do we translate the ‘universal’, when we leave Europe? And from that, that this requirement of the universal, which we had comfortably placed in the credo of our convictions, based on obvious facts, finally becomes salient, that it emerges in our eyes from its banality; that it appears inventive, audacious and even adventurous.”1 Hassan Musa refuses the uniformity that jeopardizes difference and that which we might collectively call "the Other". In this sense, the paintings on fabrics stage a questioning of the obvious facts by proceeding with a syncretism of myths: heroes and heroines be they ancient, biblical, artistic, media... What is a hero(ine)? Who builds the representation? For whom and why? The artist confronts the heroes and the anti-heroes to undermine a Manichean and smoothing view established by the West. For universalism, he chooses the notion of common, "that which is shared"2. The common does not reduce culture to a single uniform, on the contrary it forms a space where differences coexist, meet and interact. Hassan Musa makes visible the common by sewing – the joining of the different – but also by the physical and pictorial dialogue of what is usually put in opposition.

1 JULLIEN, François. Il n’y a pas d’identité culturelle. Paris : L’Herne, 2016, p.10

Julie Crenn (Translated from the French)

This exhibition was featured in LE MONDE here: