TI should be a very optimistic person because I accepted the idea of discussing the problematic question of the Lagos FESTAC 1977 in few lines.

In fact, beyond the FESTAC question stands the more problematic question of Panafricanisms.The Lagos FESTAC is an important moment in the history of Panafricanisms because it was the first opportunity where Africans became fully aware of the political signification of culture as a political lever.

Thus, the « s »in « Panafricanisms » is inevitable because it enables us to consider the problematic reality of class conflict in contemporary African art.

Among the multitude of persons who produced critical literature about Panafricanism, almost everyone has his own version of what Panafricanism is.

In the first instance, the Panafricanist idea that consists of making a political category of black skinned persons. This is a racist concept, but beyond the apparent racism, the status of black skinned persons all over the world reveals situations of oppressed socio-political category.

Long before the colonial period, Panafricanism was announced in the Bible with “the curse of Canaan »:

« Cursed be Canaan; lowest of slaves shall he be to his brothers (Genesis 9:25) »

Yet, the biblical episode of Panafricanism is controversial because nobody knows the real colour of skin of Ham’s sons (1).

Apartheid Panafricanism ?

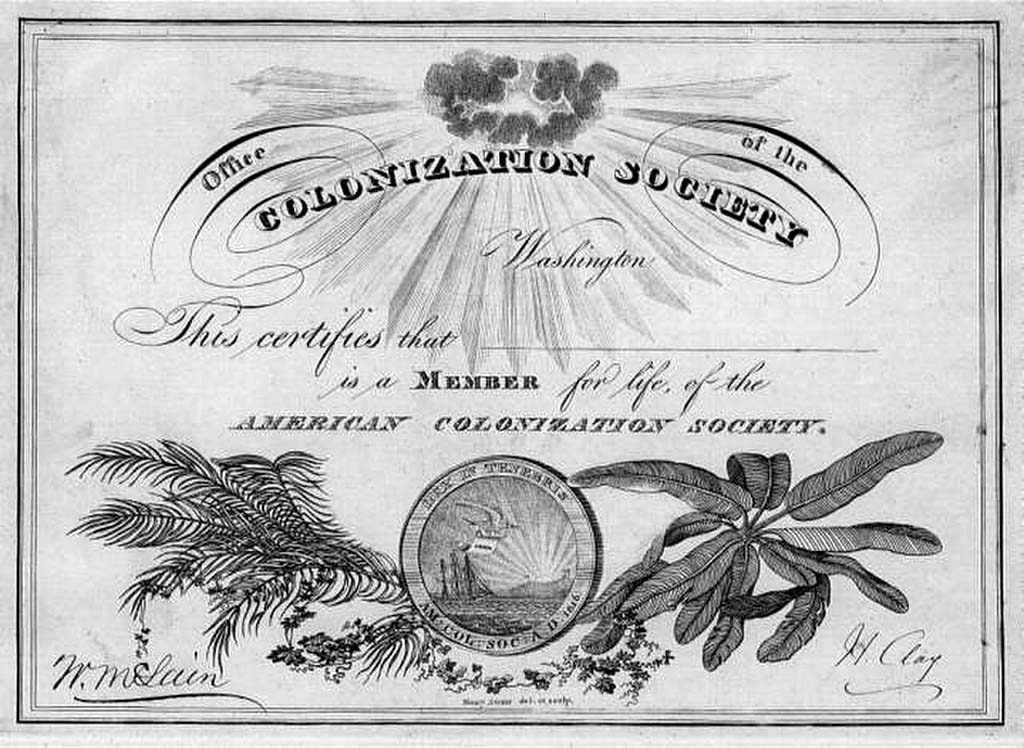

A better structured Panafricanist ideology was invented by The Society for the Colonization of Free People of Colour of America, commonly known as « the American Colonization Society »: ACS. The ACS , founded in 1816 , was a political and a religious coalition formed of Evangelicals and Quakers. They were against the integration of black persons in the American society and they preached for the « Repatriation » of free black Americans to Africa. Three American presidents, (Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe and James Madison), supported the ACS and President James Madison served as the Society’s president in the early 1830s.

Organizing the return of free black Americans to Africa, inspired the invention of an American version of coloured Panafricanism. It was also an early attempt to theorize the African continent as a matrix for a collective political identity of black persons. However the ACS’s African Utopia instigated a long tragedy for the natives of Liberia who found themselves colonized by their black brothers from the USA.Native Liberians were not considered as citizens by the black colonial caste who denied them the right to vote for more than hundred years. They were forced to work in rubber plantations for American industries such as Firestone.. That was apartheid before The Apartheid. But the situation of American freed slaves enslaving their fellow country men, enlightens the reality of memory as a flexible political object. The Liberian tragedy deprives the Negritude poets of what Jean- Paul Sartre called the memory of « fundamental experience of suffering ». In his introduction to Leopold Senghor’s « Anthologie de la Nouvelle Poésie Nègre et Malgache, 1948 », Sartre attests that « slavery is a past fact which neither our authors nor their fathers have actually experienced. But it is also a hideous nightmare from which even the youngest of them are not yet sure of having awakened. ». Unfortunately for Sartre, the Black Americans who colonized Liberia seemed to have a very short memory .«La poésie Nègre », celebrated by the Négrologues of different pigmentations, is just one possible application of the political potentiality of black memory.

The latest example of breach of memory is provided by “Black Panther”, the film of R. Coogler (Marvel Studios 2018). Everybody, except me, was happy to see the good king of the Wakanda black kingdom, collaborating with the good white agent of the C.I.A so as to prevent the international Revolution advocated by Kilmonger, the bad guy. But Kilmonger’s background reveals an Afro-American black panther was lined with a trotskist activist ready to battle against the capitalist evil.

Cold War Panafricanism ?

When Alioune Diop, founder of « La Revue Présence Africaine » (1947) and organizer of the First Congress of Black Writers and Artists in Paris in 1956, pronounced the opening speech of the Congress, it seemed natural to everyone that black artists and writers from Africa and black creators from Europe, North and South Americas, share the same dream of liberation and justice (2).

By then, international context of the Cold War(the Bandung Conference of 1955), and the evolution of the African anti-colonialist movements, created a new context that helped black communities to identify with socially oppressed categories all over the world.

The US American government viewed the Paris Congress as an international communist forum. While they couldn’t prevent the participation of Richard Wright, James Baldwin and Josephine Baker to the event, they did not allow the attendance of an important anti-segregationist like W.E.B. Dubois, was not allowed to attend the first international black assembly where Panafricanism found international political support from the anti-colonialists and the anti-imperialists across the world.

Some of the participants were considered close to Marxism by the West, but although, a marxist influence was present among some African delegations, a dialogue was established beyond the question of colour, between different cultural sensibilities concerned with social justice and anti colonialist fight.

In his declaration, Alioune Diop emphasized the slave trade as « the dominant event » in the history of black communities in the USA, the Antilles, and Africa. « It is undeniably common that we descended from the same ancestors ». Diop words go further than just paying an homage to an aestheticized black memory.They define a frame for a modern version of black Panafricanism.

Slave trade is not just a crime against humanity. It is also the longest collective trauma in the history of modernity. But Alioune Diop missed an opportunity to define a larger horizon for the black Utopia. A horizon larger than the slave trade trauma, larger than the racial and political borders imposed by the arbitrary colonial cutting of the world. Alioune Diop’s black Panafricanism confines Africans into a narrow ethnic cage, inspired by a fictionalized « common ancestors »of black people. Nobody knows the exact colour of the Africans. Africans are not all black skinned persons and all black skinned persons are not necessary Africans. The same argument is applicable to white skinned persons or to « yellow» skinned persons. Recently an interesting debate occupied the European media when the French football team, composed with many black players, won the World Cup 2018. The debate, which concentrated on the ethnic identity of black players, revealed the conservative European attitude that failed to accept the ethnic diversity of Europe, the same way they failed to accept the ethnic diversity of the Africans. The French patrons of Alioune Diop’s event preferred to ignore the African creators who were not black enough to be included in the first international Panafricanist meeting.

A better understanding of why North African writers and artists were ignored by the French Panafricanist Utopia of 1956, is possible if we examine the complex situation of French Cold War politics. North Africans presence in the black Congress of 1956 was made « incorrect » because, two years before the Paris meeting, the Algerian « Front de Libération Nationale » (FLN) started its armed struggle against French colonial presence in Algeria.

The Algerian war accelerated the process of independence in Morocco(March 1956), and in Tunisia(March 1956). Nasser’s Egypt, who supported the Algerian FLN fighters, nationalized Suez Canal ( July 1956), opening what became the « Suez Crisis »where France, the UK and Israel invaded Egypt.

Négritude Panafricanism ?

The political success of «the First International Congress of Black Writers and Artists” (1956), inspired the European organizers to explore the newly discovered lever of African Art. Thus the « Second Congress of Black Writers and Artists » took place in Rome (March 1959). Yet, the political success of the Congress, reveals a double edged sword :The French colonial authorities hoped to contain the anticolonialist movements initiated in North Africa and the black intellectuals of the world, hoped to use the opportunity to spread their own discourse about their social destiny. So, the Rome congress was designed (by France, Italy and the UNESCO), to prepare a bigger celebration of black cultures in Africa (Dakar 1966).

The declarations and the debates in Rome meeting were dedicated to the culture of sub-Saharan Africa, to the identity of black people, to black literature in North America and to the situation of black communities in South America. Alioune Diop payed homage to the genius of the Négritude as an «ongoing ambition to show the world the dignity of black race»(3).

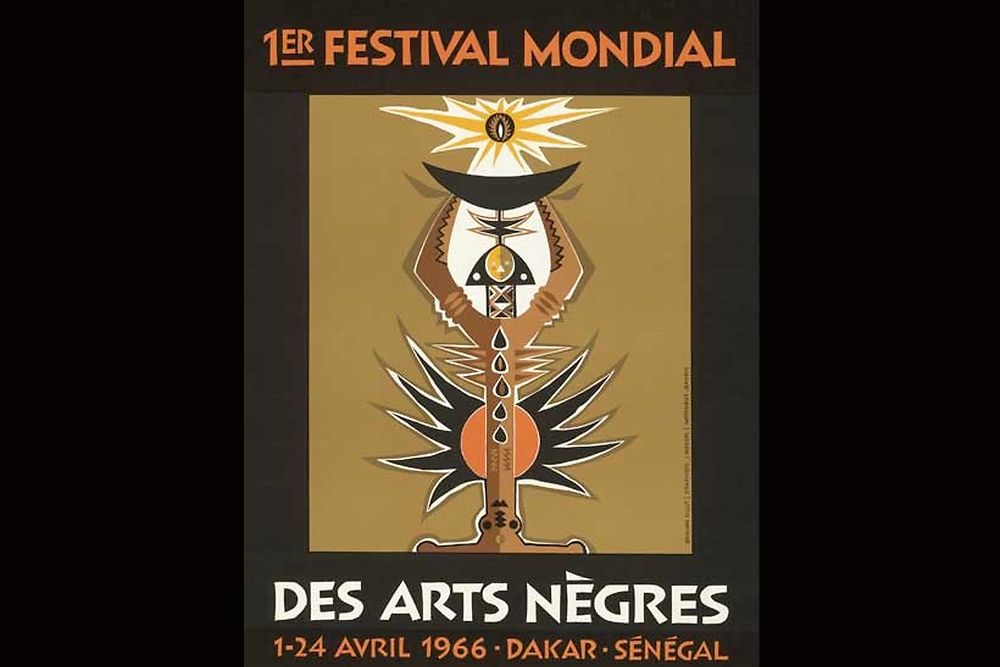

The International Festival of Black Arts(“Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres”), celebrated in Dakar in 1966, consecrated the Négritude as an ideological matrix for the production of black artists, but on the political level, France, through the words of its Minister of Culture, André Malraux, wished to see the Dakar event to the loftiness of « the destiny of the continent »(4). President Senghor’s Senegal was assigned the huge burden of the watchman for French interests in Sub-Saharan Africa. The enthusiasm of Malraux and Senghor enlightens their common religious belief in the efficiency of art as an instrument of social change in Africa. But both seem to forget that social change is also about access to economic development, democracy and human rights. During the Cold War tensions, nobody, in Europe or in the USA, was ready to expose his African interests to the risks of democracy and real economic development. Africans were abandoned in the longest «huit-clos» in History with the worst tyrannical rulers.

Today, if black African communities suffer the misery of low literacy rates, then one might ask : for what kind of readers do the Black African writers write ?What I know is that the best market for the contemporary African literature is in Europe and in North America. May be this is why the Négritude business is kept confined in the dark continent of the European middle class litterary tradition.

Tigritude Panafricanism ?

In December 2017, I had an interesting encounter with contemporary African art in Khartoum. Professor Salah Hassan,who was invited by the « Sudan Film Factory », presented an interesting documentary film about the « Dialogue » (2015) between Senghor and Soyinka as imagined by Manthia Diawara, a Malian film maker, based in the U.S. Diawara organized diverse archived documents to create a « dialogue » between the two grand icons of the 20th century African culture. After the projection, the enthusiastic audience of artists, writers and young film makers couldn’t avoid the « usual » debate about Sudan’s cultural identity between Arabism and Africanism options. Manthia Diawara’s film reactivated the long and rich debate about Art and Politics in Sudan. This intellectual experience makes it difficult, for Sudanese artists of today, to accept the possibility of a contemporary African art based on ethnical arguments. May be because the Panafricanist attitude of the older generation of Sudanese artists at the « Khartoum School », inspired by the local political history of the Sudanese civil war, opposes the cultural mixing principle against the narrowness of the Senghor’s pure Black Panafricanism , as celebrated in the «Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres» in Dakar (1966).

But, at the same time, the « Khartoum School » artists, Ibrahim El-Salahi, Ahmed Shibrain, Kamala Ishaq, etc…, were not enthusiastic to join the revolutionary anti-imperialist Panafricanism celebrated in the «Festival Panafricain d’Alger» in Algeria (1969),that was dedicated to liberation movements in Africa and in the Afro-American communities in the world.

El Salahi , who was the Undersecretary of Sudanese Ministry of Culture, organized the Sudanese participation in Lagos FESTAC 1977, just before he got arrested for conspiracy against the Nimeiry’s regime.

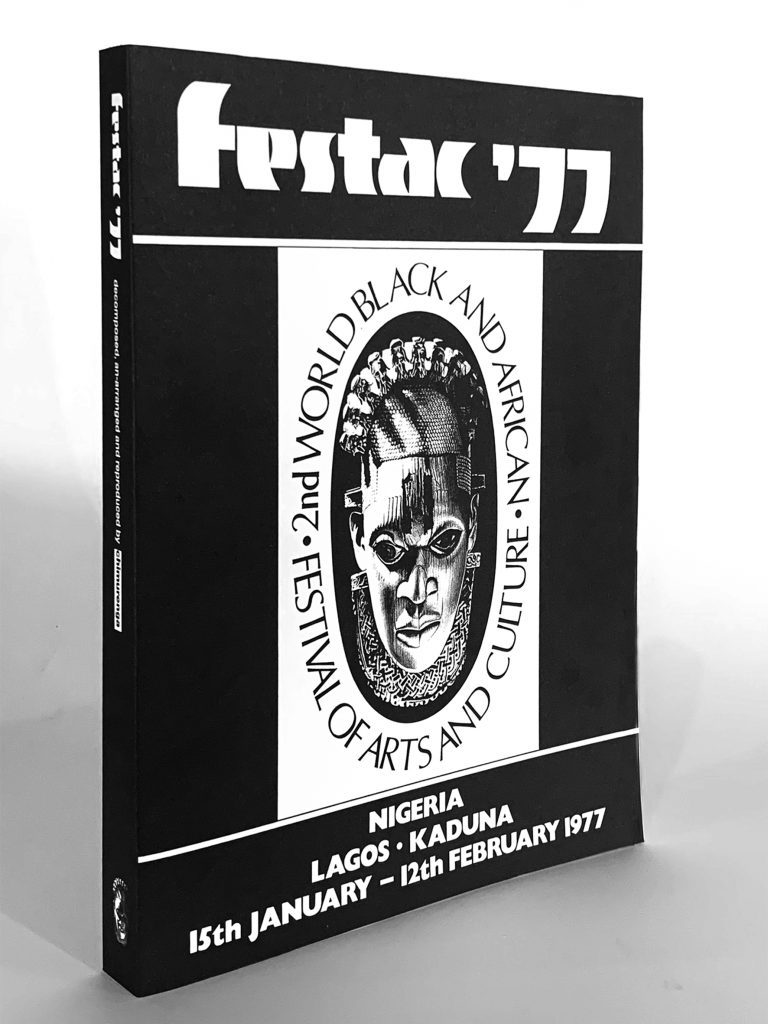

For the Sudanese, the Lagos FESTAC 77 was a sort of third way between the Négritude Panafricanism and the Algerian Anti-imperialist Panafricanism. The Nigerian authorities had to change the name of the festival from “World Black Festival of Arts and Culture” to “Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture” so as to accommodate the realities of African Unity and the post civil war period in Biafra. The FESTAC 77 organizers were inspired by an open Panafricanist attitude beyond the racial or geographical barriers. Henceforth the Lagos festival was opened to all Africans with total indifference to the geographical or the ethnic criteria. The Senegalese officials considered the change as a treason to the spirit of the Dakar festival.Consequently, the respective national presses of Senegal and Nigeria picked up the banner and transformed the debate into an affair of national honor. If this debate failed to entangle other African countries, it was because the majority of observers knew that behind the quarrel over abstract concepts lay the geopolitical situation of the Cold War in Africa. The regime of the father of Négritude, who spoke in the name of French-speaking countries in sub-Saharan Africa, and indeed in the name of France, found itself in a critical situation, divided between the dominant Pan-African feelings of the post colonial period and the political will of France, to which it owed everything, and which, some years earlier, had made no secret of its complete support for secessionists in Biafra, the principal zone of oil production in Nigeria, at that time.

The Soyinka/Senghor quarrel was not about democracy, development or human rights in Africa. It was about the obsessions of the new African middle class intellectuals raised under the colonial period. Facinated by uncertain concepts like the essence of the” Nègre” or that of the “Tigre”, the real identity of the African and the multiple qualms about diaspora (5), these guys couldn’t see the social priorities of the Africans. This is why the dispute between the “Négritude” and the “Tigritude”, vanished with the end of the Cold War period. For a while, the opposition between Senghor and Soyinka became a question of research workers in Political Sciences of African modernities. This brings us back to Diawara’s film. Salah Hassan(6), who is an eminent figure in the contemporary African Art scene, presented the M. Diawara film for the 2017 Khartoum audience, in a different perspective: the global African art perspective.This recent “ renaissance” of “the African thing” in the international art scene owes its success to the globalization of the so called: “contemporary African art”. The patrons of the Contemporary African Art reinvented a new version of Panafricanism designed to perpetuate a conservative racial image of African culture.

In Europe, Jean-Hubert Martin, the French curator of “Magiciens de la Terre”(1989), initiated a French version of the global ethnicization of the World with exhibitions like “Partage d’Exotisme -Each culture is exotic to the other cultures”(2000).

In the USA, people like Susan Vogel, curator of “Africa Explores”(1991), prepared the American scene of African Art to be the New Liberia of the Afro-American artists, a sort of black Indian Reserve to receive Afro-American artists as part of a new Biblic category defined as the global African Diaspora. Well, if Black Americans, sent back to “Mother Africa”, colonized their Liberian blood brothers for long time, then African artists should worry about their future in this global version of African art.

The Arab Panafricanism ?

Like most of the African persons of my generation I have a very approximative knowledge about what some scholars call :« African cinema». So, when Salah Hassan presented Manthia Diawara as an African « specialist » of African cinema, I was enthusiastic to learn more about his work. If you google M. Diawara’s name – as I did- you will find that M. Diawara belongs to this category of African «international experts» envolved in teaching«l’Art Nègre» to the world. When I say :« teaching l’Art Nègre », I refer to the Picasso/Leiris’s story about the young Cuban artist, Wifredo Lam. In1938, Picasso asked Michel Leiris to teach Lam «l’art nègre »(7).The strange request of Picasso seemed natural at that time where the Primitivism was well established as an aesthetic option legitimized by the Fauves, the Dadaists, the Surrealists, the Cubists etc…The main idea in Picasso’s advice is that « L’art nègre » is something that can be taught. Since that time, Lam’s work became a model for the African version of Primitivism for contemporary African artists. But Lam is not exactly African, he was born in Cuba from a Cuban father of Chinese origin and a Cuban mother of African and Spanish origins. Yet the Chinese origin of Lam was of no interest for the Négrologues of the French “Artafricanisme”(Who cares about Obama’s white mother?).

The ”Art Nègre” misconnection ignored the Chinese father of Lam the same way the Contemporary African Art curators ignored the Arabic connection of Ibrahim El Salahi when his work was presented at the Tate Modern(2013). Nobody mentioned the possible connection of Salahi with the work of the Lebanese sculptor Rawda Choukair whose work was shown next door to Salahi’s show, in the Tate Modern. I suppose nobody wanted to see Salahi as an Arab artist also. He just can’t be in supposed “two places” at the same time!.This “Arab place” of the African artists seems to be the Achille’s heel of all the Négrologues of contemporary art(8). If we examine the Manthia Diawara’s film in this perspective, we find that Diawara organized his version of Panafricanism without mentioning the North Africans contribution to the elaboration of new Panafricanism. Diawara’s film mentions many documents concerning the historical celebrations of important Panafricanism events:

-The 1956 “Congress of Black Writers and Artists”(Paris).

-The 1959 “Congress of Black Writers and Artists”(Rome).

– The 1966″World Black Festival of Arts and Culture”(Dakar).

– The 1977 “Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture”(Lagos).

In his historical account, Diawara seemed less interested by the Algerian Panafrican Festival of 1969. The Omission of the 1969 “Festival panafricain d’ Alger” impoverished the “Dialogue” between Senghor and Soyinka because it made it look like a duel between two refined essentialisms:” Négritude/Tigritude”, while the introduction of African liberation figures in the debate could have opened larger horizon about the kind of cultural development needed in African societies. Omitting the 1969 Panafrican Festival of Algeria put Manthia Diawara’s film in the suspicious category of the Négrologues who are unwilling to accept the ethnical and cultural diversity of the African society. Nevertheless, it is on the basis of this accepted diversity that the National Liberation Front of Algeria supported the South African African National Congress fighters with arms and training.“Mandela received his initial military training by the rebels of the National Liberation Front in Algeria in the early 1960s”(…) “Algeria was a strong supporter of the African National Congress, providing it with weapons, passports and other tools which contributed to the historic triumph against Apartheid”(9). Further, the omission of the 1969 “Festival Panafricain d’Alger” denotes the deletion of the political dimension of culture as an arm of liberation. The official manifest of the 1969 festival, as pronounced by Houari Boumediene, the Algerian President, accentuated the importance of culture in the anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist fight in Africa. Almost all the representatives of African Liberation movements were present in Algeria. Freedom fighters from Angola, Namibia, Guinée Bissau and south-Africa,were standing side by side with leaders of black communities in Europe and the USA (including Black Panthers leaders, Bobby Seale, Eldredge Cleaver and StokelyCarmichael).

White Negros’ Panafricanism?

In his “Discours sur la Négritude”(10) Aimé Césaire remembers his amazement when, at first visit to Québec, he came across a bookshop showing a book with a confusing title: “We, White Negros of America”. Césaire concluded that the author of the book understood everything about the Négritude”.Senghor and Soyinka would have considered such a title as a flagrant violation of identity.

Notes:

(1)

The later repression and discrimination against the freed black slaves( in the USA) received as much biblical and Christian support as the earlier institution of slavery itself. This discrimination and the enslavement of blacks only, was made on the basis of what has become known as the “sin of Ham” or “the curse of Canaan . »

« .. » In retaliation for Ham’s sinful act of seeing his father nude, Noah puts a curse on his grandson (Ham’s son) Canaan:

Cursed be Canaan; lowest of slaves shall he be to his brothers (Genesis 9:25)

Over time, this curse came to be interpreted that Ham was literally “burnt,” and that all his descendants had black skin, marking them as slaves with a convenient colour-coded label for subservience. Modern biblical scholars note that the ancient Hebrew word “ham” cannot be translated by “burnt” or “black.” Further complicating matters is the position of some Afrocentrists saying that Ham was indeed black, as were many other characters in the Bible.

(2)

Among participants of the « 1st Congres des Ecrivains et Artistes Noirs » (1956), there was Aimé Césaire, Frantz Fanon, Edward Glissant (Martinique), René Depestre, Jean Price Mars (Haïti), Marcus James (Jamaïque), Jacques Rabemananjara (Madagascar) Cheikh Anta Diop, L.S. Senghor (Senegal), Gerard Sekoto (South Africa), James Holness (Jamaïque), Amadou Hampâté Bâ ,(Mali), J. Vaughan (Nigéria), M. Dos Santos (Mozambique)…

(3)

Deuxième Congrès des écrivains et artistes noirs (Rome : 26 mars-1er avril 1959). Paris, Présence africaine, 1959.

(4)« For the first time a chief of State holds in his perishable hands the destiny of a continent » Opening speach of André Malraux,1st of April 1966, le premier Festival mondial des arts nègres.

(5)

In a Kampala declaration of 1962, Soyinka said that a tiger does not shout its tigritude, it pounces. Similar statement was made by Soyinka in Berlin,1964:When you pass where the tiger walked before and you see the skeleton of the gazelle, you know some tigritude has emanated there. In the dispute about Lagos FESTAC 77,some Nigerians brought the words of Soyinka to the scene while other Senegalese opposed Senghor’s word: “Le Tigre ne parle pas!” .(The tiger can’t speak).

(6) http://africana.cornell.edu/salah-m-hassan

(7)

Jean Louis Paudrat ,Lam métisse ,Musée Dapper, 2001

(8)

I use the terme”Négrologues” after Stanislas Adotevi’s title:Négritude et Négrologues ,Paris,1972

(9)

(10)

Aimé Césaire ,Discours sur le colonialisme, suivi de Discours sur la Négritude ,Présence Africaine, 2004.